Bexar County Commissioner Kevin Wolff is bringing a resolution to a vote on Tuesday, February 17 (see Item #69, on page 13 of the Commissioners Court Agenda) to reaffirm that he wants to impose toll taxes to drive US 281 (from Loop 1604 to the county line) and I-10 (from Loop 1604 to Boerne), and Loop 1604 (from Bandera Rd. to I-35 at the Forum).

Call Kevin Wolff‘s office NOW at (210) 335-2613 to urge him to pull down his resolution and use the new road money from Prop 1 (avg. $1 billion/yr) and the money coming shortly in the next budget to be adopted by the Texas Legislature (at least $1.2 billion) to fix these freeways without TOLLS! View the plan here.

What will it cost me?

The published toll rates range from 17 cents a mile – 50 cents a mile. Wolff and his fellow commissioners along with his Dad, County Judge Nelson Wolff, will impose ‘congestion tolling,’ to ensure you pay the maximum to use the toll lanes during peak hours (when everyone actually has to get to work).

So these new toll taxes will average $8-10 day or over $2,000 a year in new taxes just to get to work. The more congestion on the roadway, the more you pay. In fact, the toll rate rises in real time to purposely knock cars out of the toll lanes if the speed drops below 50 MPH in the toll lanes, which is almost guaranteed behind a bus (these will be HOV-toll transit lanes, also called ‘managed lanes’)!

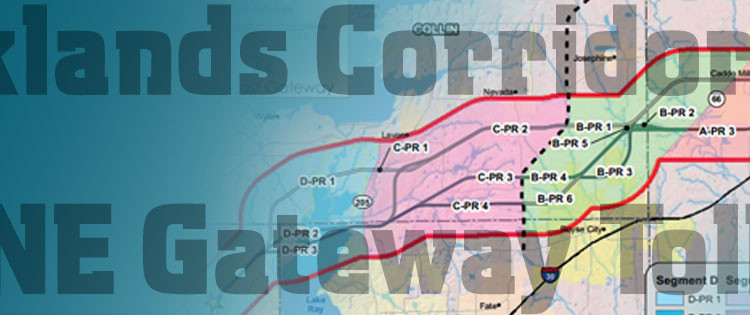

What’s the plan?

View the plan here.

On US 281, today there are 5-6 freeway lanes from Loop 1604 to Stone Oak Pkwy. When they’re done, there will still be just 6 lanes of highway, BUT, one existing freeway lane in the center will be converted into a HOV-toll transit lane (think bus lane, you’ll be paying a toll to drive slow behind buses, also called ‘managed lanes’ to hide the word ’toll’). No new highway lanes will be added at all, yet the toll authority (Alamo RMA) is conducting a half a million dollar ad campaign that tells commuters the toll road will DOUBLE existing capacity. All they’re adding are access roads, not highway lanes. So they’re counting the new frontage roads as ‘doubling your capacity.’

These HOV-toll lanes have NO ACCESS to Loop 1604 (on either proposed toll project) so if you need to get on 1604, you’ll be stuck in the congested general purpose lanes. On US 281, there’s also no exit for any local traffic until Stone Oak Pkwy, so commuters cannot access all those neighborhoods from the toll lanes, leaving more cars on the congested freeway.

North of Stone Oak Pkwy on US 281 there are 4 existing freeway lanes today. When they’re done with the freeway-tollway conversion, every single free lane will be converted into a toll lane. Commuters will have NO free highway option on the northern stretch of US 281 (from Stone Oak Pkwy. to the Bexar County line).

On I-10 and Loop 1604, the plan is to add two new HOV-toll transit lane each direction (although some documents only show one new lane on I-10). At Loop 1604 & I-10, the new direct connect interchange ramps will NOT be accessible to anyone other than those paying tolls. In both the I-10 & US 281 corridors, buses will have very expensive, exclusive direct connect ramps into/out of the toll lanes to Via’s park-n-ride transit centers in the Hill Country (where few will ever carpool or get on a bus). On US 281, the toll lanes do not connect to Loop 1604, and you’ll be paying a toll to get stuck behind a bus. If I-10 is one lane and not two, you’ll be paying a toll to get stuck behind a bus there, too.

Why now?

While both Wolffs have consistently voted to toll our area freeways, why are they voting to ‘reaffirm’ something they already did? Because former Gov. Rick Perry’s Transportation Commission Chairman Ted Houghton is being replaced in just a few short weeks by incoming Governor Greg Abbott who campaigned against toll roads. Houghton and Perry have made it their mission to impose tolls all over Bexar County, and they’ve been unsuccessful due to citizen resistance. If the Commissioners pass this resolution, they’re attempting to thwart the efforts by Governor Abbott and the Texas legislature to fix the road funding shortfall without more tolls and hence get Bexar County freeways fixed toll-free as promised.

Bait & Switch – Broken promises

Sadly, when Nelson Wolff was running for re-election he sent a letter to the Transportation Commission to ask for Prop 1 money to be used to fix US 281 without tolls, now that he won re-election, he’s reneged on his promise and is voting to keep tolls on US 281.

TAKE ACTION

Call Kevin Wolff’s office NOW at (210) 335-2613 to tell him to pull down his resolution and use the new road money from Prop 1 (avg. $1 billion/yr) and the money coming shortly in the next budget to be adopted by the Texas Legislature (at least $1.2 billion) to fix these freeways without TOLLS!

For more history, go here:

– SA officials unveil $825 million toll plan

– Board reneges on promise to fix 281, 1604 without tolls

– Wolff flip-flops: ‘You can fry me for it later’

Public-private transportation partnerships continue to fail around the world. The Spanish-Australian consortium that runs the Indiana Toll Road became the latest casualty seeking Chapter 11 protection in the US Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois. On Tuesday, Judge Pamela S. Hollis began hearing the case.

Public-private transportation partnerships continue to fail around the world. The Spanish-Australian consortium that runs the Indiana Toll Road became the latest casualty seeking Chapter 11 protection in the US Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Illinois. On Tuesday, Judge Pamela S. Hollis began hearing the case.